Dan River management did not include indoor plumbing for toilets in any of the mill houses until well after Schoolfield was annexed by the City of Danville in the 1950s. Until annexation, most Schoolfielders only had access to water through an outdoor spigot, and access to baths and indoor bathrooms available at the Welfare Building and Hylton Hall for small fee. The company also provided toilet facilities in their mills, weave sheds, and dye houses but the company only provided wood-frame outhouses in the backyards of Schoolfield homes. As Schoolfielder Nell Collins Thompson remembered in her memoir of the village’s early years, “slop jars were often made use of, especially at night” in addition to the outhouses, better known as privies.

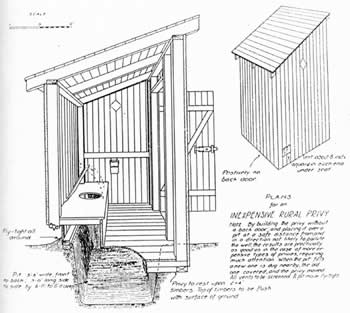

Though none stand today, millhands’ residences had a dry privy, most likely of the “box and can privy” type. Box and can privies were outhouses common to communities with 300 or more houses and were usually handled by a municipality or a large private company for upkeep and sanitation. Box and can privies featured a water-tight receptable placed in the ground beneath the seat. These receptacles would store waste for a short period of time, but required costly regular removal and disposal to maintain sanitary conditions. Additionally, this type of privy left waste vulnerable to extreme temperatures. Waste would often freeze in their receptacles during the winter months, making collection and removal a difficult process. In the summers, waste was heated with the rise in temperature, causing “objectionable odors” to permeate throughout residential areas.

Though these privies could be unpleasant, they were not uncommon in Danville, southern mill villages or the south as a region. In southern mill villages, seventy percent did not offer indoor or flushing waste facilities. In the south, as one 1909 report on southern sanitary conditions found, only a third of farming households and handful of rural white households had a privy at all; most rural families simply relieved themselves in the back of the barn or some nearby woods. Privies at private residences in Schoolfield and especially the indoor facilities on the job thus were often a step up to the first generation of Schoolfield millhands, who likely grew up with unsanitary privies or no privies at all on rural farms.

Where and how millhands relieved themselves became an object of ridicule both to insiders and outsiders of the Schoolfield community. In one instance, a middle-class, white Danville reporter, Julian Meade, centered his snickering of millhands’ backwardness on one particular white millhand named Capitola, who he described in his 1935 book I Live in Virginia. Capitola, Meade observed, was a “sallow-faced girl” whose backwardness was evident in her “hat[ing] all Negroes,” and fear of “trains, telephones” and other “manifestations of American progress,” including the flushing toilets at the mill. Meade recalled that Capitola’s friends teased her for being “still impressed by the ladies’ rest room” at the mill, where she worked pressing pillowcases. Having come to Schoolfield from a “remote mountain section,” Capitola’s amazement at the mill’s indoor plumbing was prime fodder for ridicule and Meade gleefully related how her fellow millhands mocked Capitola, saying “we ought to put some pine brush by the door [of the ladies’ rest room] so Capitola can tell where she’s at.”

Millhands did not simply take this type of ridicule, but often reflected it onto others in the village, particularly the Black men who drove the “honey wagon” that cleaned out the outhouses on a regular basis. Nell Collins Thompson related one such story in her historical memoir of Schoolfield village life. “It was said,” Thompson writes, “that one day the driver [of the honey wagon] dropped his coat into the contents of his wagon. He went to the rescue but his helper said, ‘Leave it alone. It was old anyway, wudn’t it?’ ‘Yeah,’ replied the driver, ‘but it had my lunch in the pocket.’”

Outhouses in Schoolfield were likely similar to this privy shown here. Courtesy of William & Mary’s archaeological study of Dan River homes in North Danville.

This 1949 article from the Danville Register decries the City’s outhouses and the move to annex Schoolfield, which the City eventually did do in 1951. Courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection Dan River Inc. Papers.

This 1951 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map shows the alleys in the southern section of the village that once existed behind all Schoolfield houses. These alleys were tread by the “honeywagon” that cleaned out Schoolfield privies. Courtesy of the Salem Public Library.

See also:

Thompson, Nell Collins. Echoes from the Mills. Roanoke, Virginia: Toler Printing Co., 1984, p. 26.

Neill, Charles P. “Chapter VIII. The Mill Community.” In Report on Condition of Woman and Child Wage-Earners in the United States, 517–612. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1910. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/osu.32435026689562.

The Sanitary Privy. Public Health Reports, Supplement 108. Public Health Service, 1933. http://hdl.handle.net.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/2027/osu.32436001154598, pp. 37-8.

Elman, Cheryl, Robert A. McGuire, and Barbara Wittman. “Extending Public Health: The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission and Hookworm in the American South.” American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 1 (January 2014): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301472, p. 49.

Helena, Safron. “Memorializing the Backhouse: Sanitizing and Satirizing Outhouses in the American South.” Accessed October 27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.17615/BQMS-SV22, p. 39.

Meade, Julian R. I Live in Virginia. New York & Toronto: Longmans, Green & Co., 1935. https://archive.org/details/iliveinvirginia008017mbp.