Like many other textile companies in the South, Dan River provided housing for their workers in exchange for rent. In developing their mill housing in Schoolfield in the early 1900s, Dan River management relied on best practices in mill village residential design as set forth by a fellow southerner, Daniel Tompkins. Tompkins, a southern engineer and architect who had had northern training, advised that mill villages maintain just enough rustic charm to make their formerly rural inhabitants—which most millhands were—feel at home in a new industrial urban environment that came with new, industrial work. In his 1899 textbook on southern industrial design, Tompkins suggested that southern mills depart from the northern company town practice of row houses and build detached, single-family mill homes spaced at least seventy-five feet apart from the center of one house to the other. With space between and behind and backyards that provided enough room to garden, raise chickens, hang washing, and have a bit of privacy without isolation, houses laid out by Tompkins’s rules attempted to accommodate rural workers, easing them into industrial work and urban life.

Schoolfield’s housing stock reveals strict adherence to some of Tompkins’s textbook rules.With rare exception, all early twentieth century homes in Schoolfield were plotted seventy-five feet apart from one another, though on smaller plots that were often a third of an acre rather than Tompkins’s prescribed half-acre. Houses were clustered near the street with abbreviated frontage anywhere from twenty to thirty feet. Small front yards were buffered from the street with intermediary porches on all the homes. Behind the homes stretched large back lots bounded with the “best grade of wire fencing” to encourage gardening, but also gave an ordered, “uniform appearance” that was “much to be desired,” in the opinion of Dan River Welfare Superintendent Hattie Hylton. Along with gardens stood small wooden privies in the backyard, relieving the company of installing an expensive sewage system for indoor plumbing, which executives deemed unnecessary for their rural mill recruits.

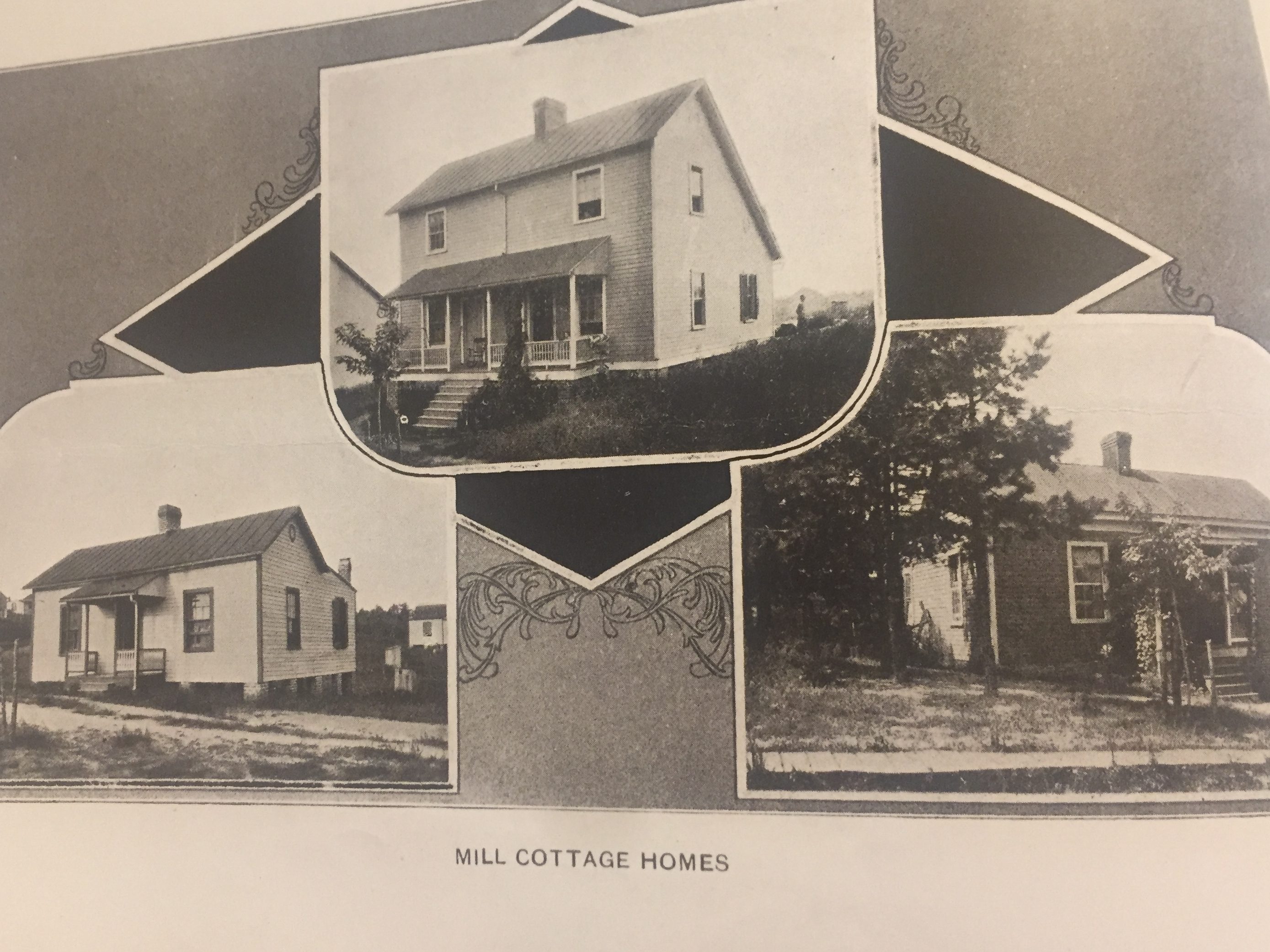

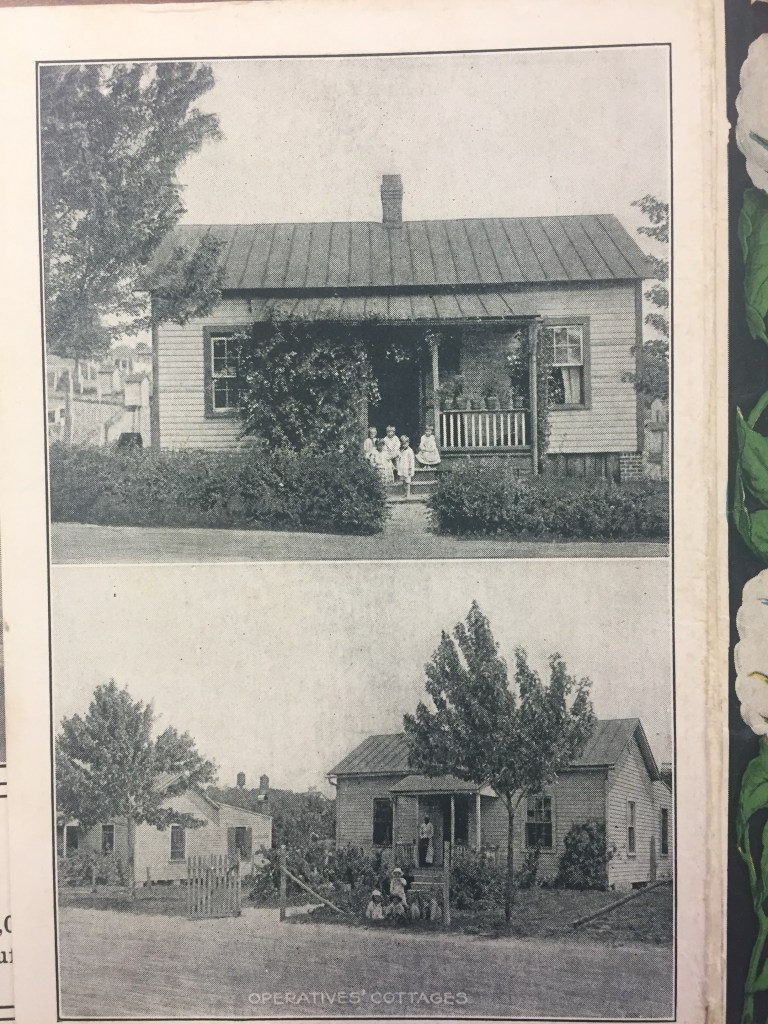

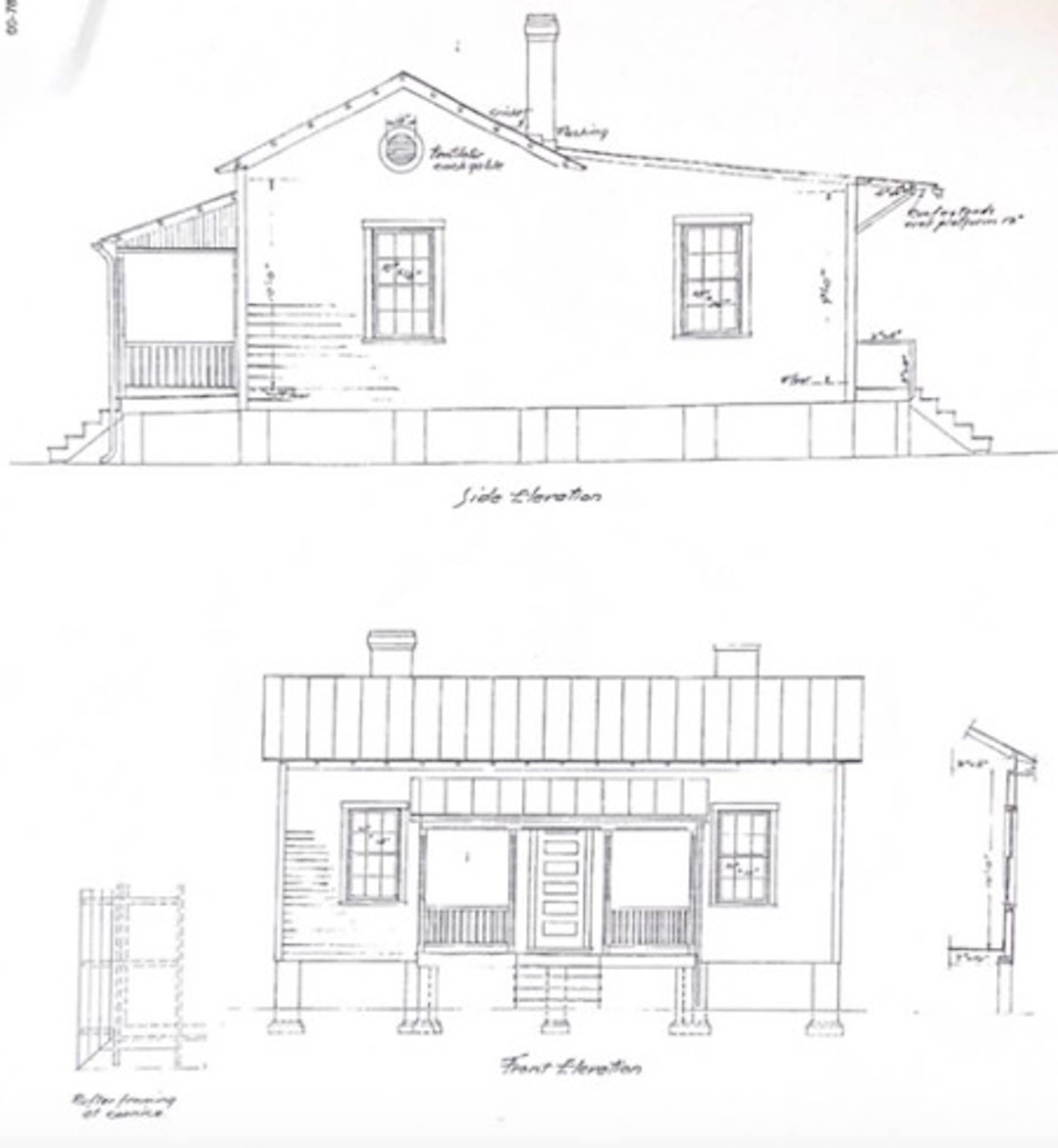

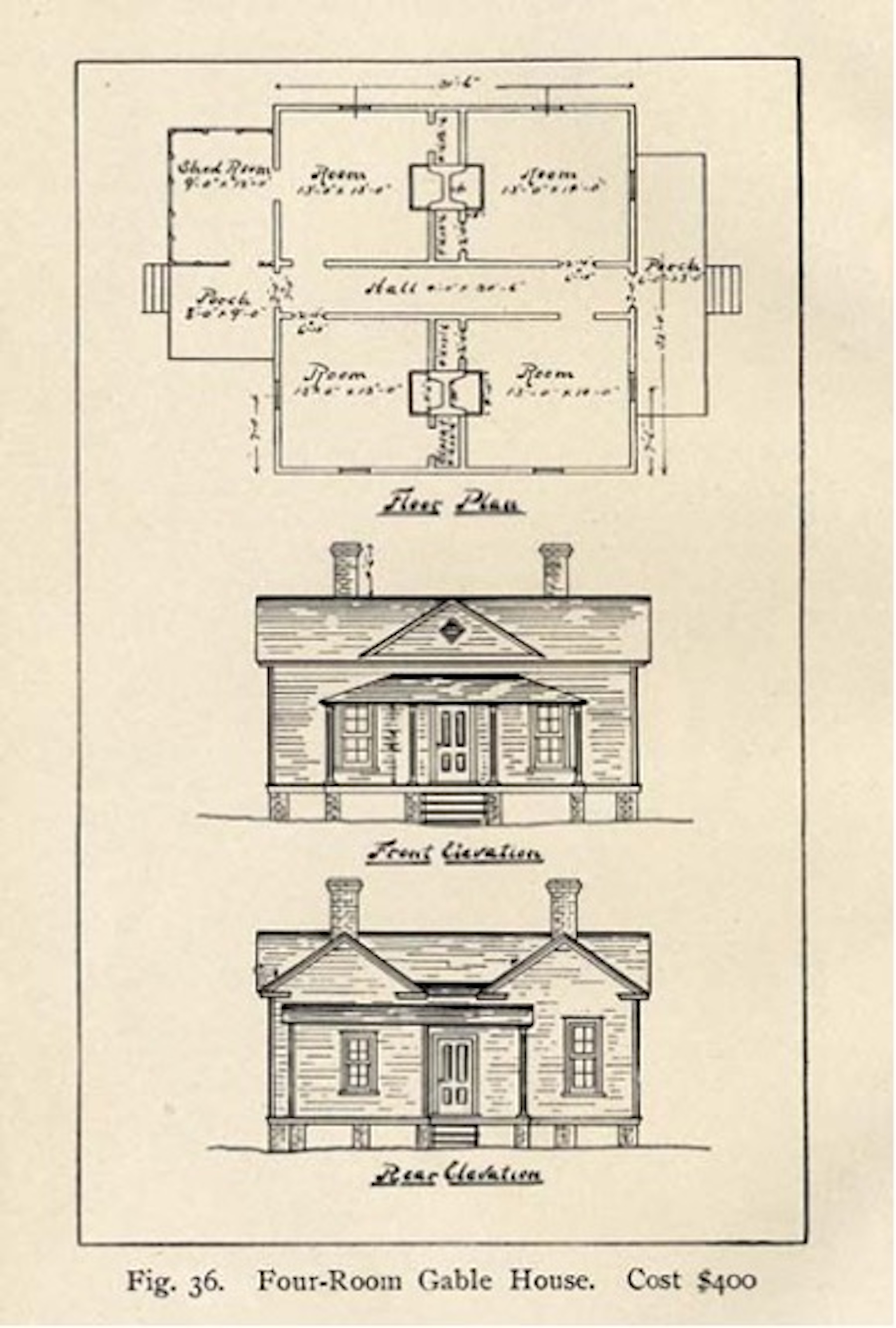

Under Dan River founder and board member T.B. Fitzgerald’s architectural direction, Schoolfield’s first 220 workers cottages were built along the first six residential streets in the northern section of the village. Oak Ridge, Bishop, Wood, Spencer, Water, and Park curved to the West, North, and East of the central mill site, though on a lower topographical plane. The unvaried style of these homes was mirrored in the bulk of residential inventory in the fifteen streets Dan River developed in the 1910s in a southern area of Schoolfield such as Stokesland. Lined up along sloping northern and southern streets of the village, Schoolfield’s homes followed a repetitive pattern of six, four, three, and two-room cottages. The most typical style was a four-room house, but no matter what size or typology, nearly all Schoolfield homes bore the familiar markers of southern cotton mill design. These homes had wood shiplap exterior siding, a side-gable standing-seam metal roof with one or two interior brick chimneys, double-hung wood-sash windows with six-over-six lights, and a partial-width front porch with simple wood post supports. The larger six-room homes had dormers extending from the front and rear roof planes on a rare half-story above the first, and some homes had decorative vents beneath their roof gables. For the most part, however, these homes had little ornamentation or variation. Even the wood was all of the same kind: North Carolina pine, single sourced from the Snow Lumber Company in High Point, who furnished lumber for frames, weatherboarding, flooring, window sashes and doors of these early homes.

The interiors of these homes were just as simple. Most of these one-story wood-frame homes drew from a traditional British folk form, the hall-and-parlor form, which developed into the larger massed-plan form popular in the southeastern United States among mill village housing. Following this tradition, these homes were usually two rooms wide and one or two rooms deep. Whether situated in an L-shape as the three-room houses were, or a simple rectangle as four-room houses were shaped, most interior floor plans divided the rooms with a central hallway to increase ventilation, which was believed to enhance workers’ health and sanitation. Houses had plaster walls, two central interior fireplaces, a pantry in one of the rear rooms, but of course no indoor plumbing and thus no bathroom. In larger houses such as the six-room type which had one-and-a-half stories, fireplaces were placed in the two front rooms and the rear rooms were equipped with flues for wood stoves to heat the house and cook what little food they had—pinto beans from the garden, ham hock or biscuits were regular staples.

Looking down one of these Schoolfield streets, especially in the southern residential section, was like looking down an endless mirror, with some streets stretching half a mile long of nearly identical houses. Surrounded by homes of similar material and form, Schoolfielder Wally Beale recalled that in the village “you were just about all one.” This similitude changed in the 1950s, when annexation by the City of Danville and the sale of company houses brought changes to village housing stock. Among the first changes most millhands made when they purchased their homes from the company was to install indoor plumbing and upgrade their porches, often replacing the wood posts with steel and other decorative railings.

It is important to note that though many millhands became homeowners in the 1950s, Black workers, who were not allowed to live in Schoolfield, could not take advantage of the same benefit. As was typical during the era of racial segregation known as Jim Crow, housing deeds in Schoolfield forbade owners from selling their house to “any person of Negro descent” for twenty years after the sale. This restriction kept Schoolfield a segregated community of white people until broader national Civil Rights laws, such as the 1968 Fair Housing Act, made such housing restrictions illegal.

This 1950s deed of sale from Dan River Mills to a millhand family in Schoolfield clearly forbids Black people from owning homes in the village. This discriminatory practice was outlawed by the 1960s.

A Dan River promotional pamphlet showcasing the (slightly) different styled homes that they offered to millhands.

A portion showing operatives cottages in a 1917 Schoolfield promotional postcard. Courtesy of Carol Handy.

Architectural renderings of mill housing in Schoolfield. Courtesy of Virginia Department of Historic Resources alongside the 1899 suggested plans as specified by Daniel Tompkins.

Excerpt of a June 1916 report on Schoolfield and its welfare and housing programs by Hattie Hylton. Courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection Dan River Inc. Papers.

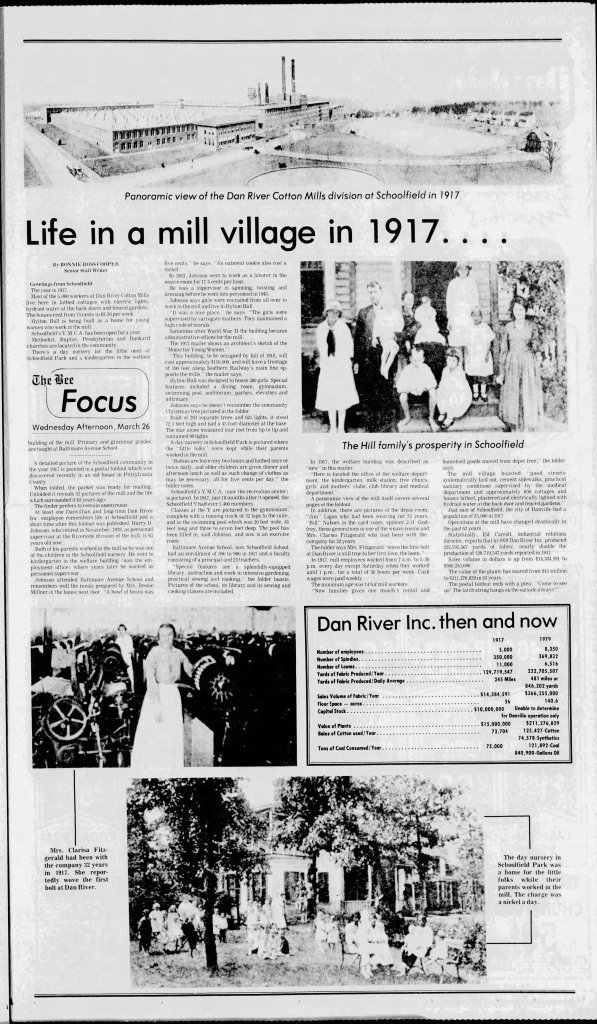

“Life in a Mill Village in 1917,” a restropective from a March 26, 1980 Bee showcase.

See also:

Rykwert, Joseph. “The Street: The Use of History.” In On Streets, 15–27. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1978.

Smith, Robert S. Mill on the Dan: A History of Dan River Mills, 1882-1950. Duke University Press, 1960, p. 256.

Virginia McAlester, A Field Guide to American Houses: The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America’s Domestic Architecture (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017), 144.

“108-5065 Schoolfield Historic District – Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Survey File,” 2000, Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond.

Thompson, Nell Collins. Echoes from the Mills. Roanoke, Virginia: Toler Printing Co., 1984. 26.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd, James Leloudis, Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, Lu Ann Jones, and Christopher Daley. Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World. 2000 ed. The Fred W. Morrison Series in Southern Studies. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987, 150.