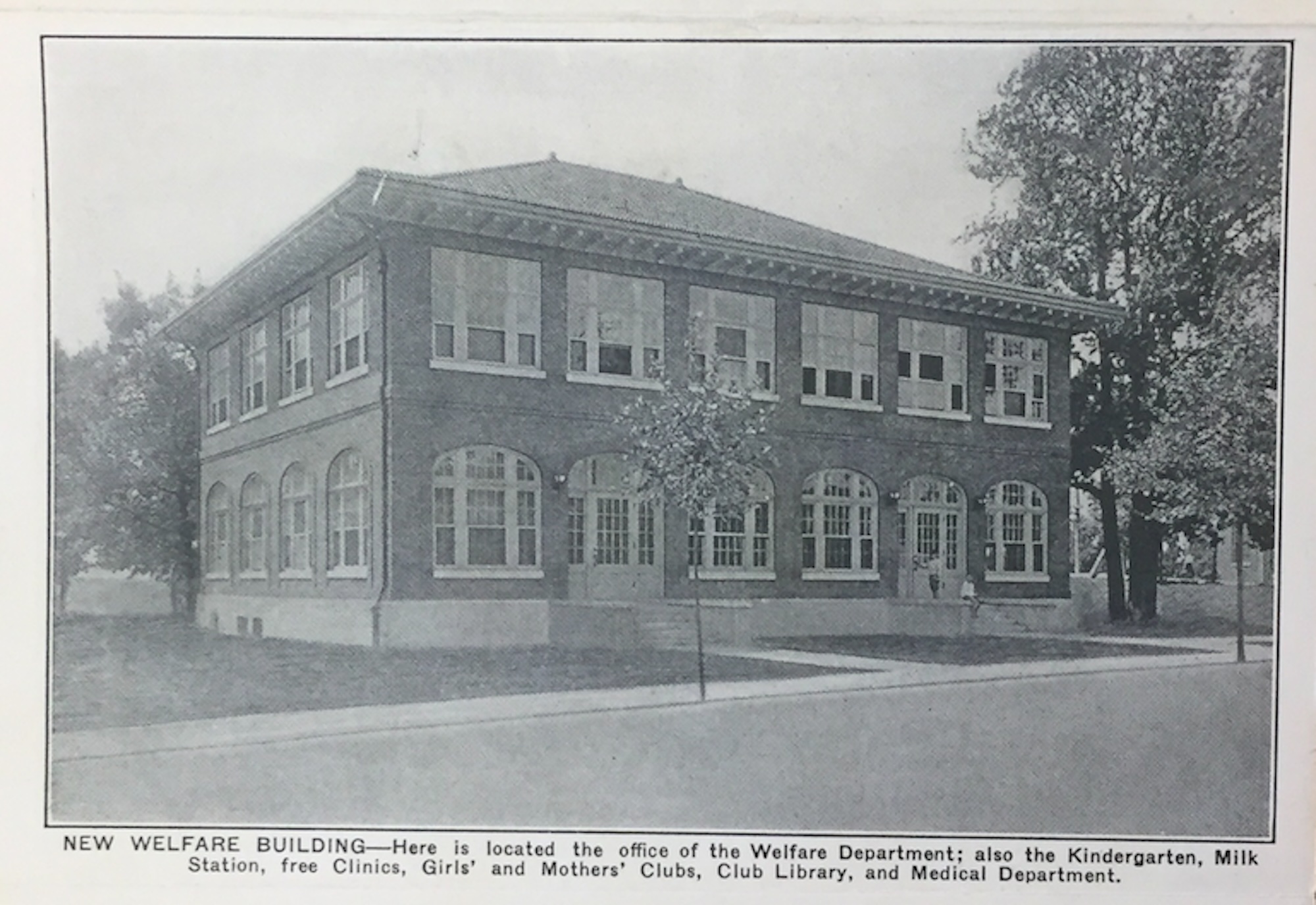

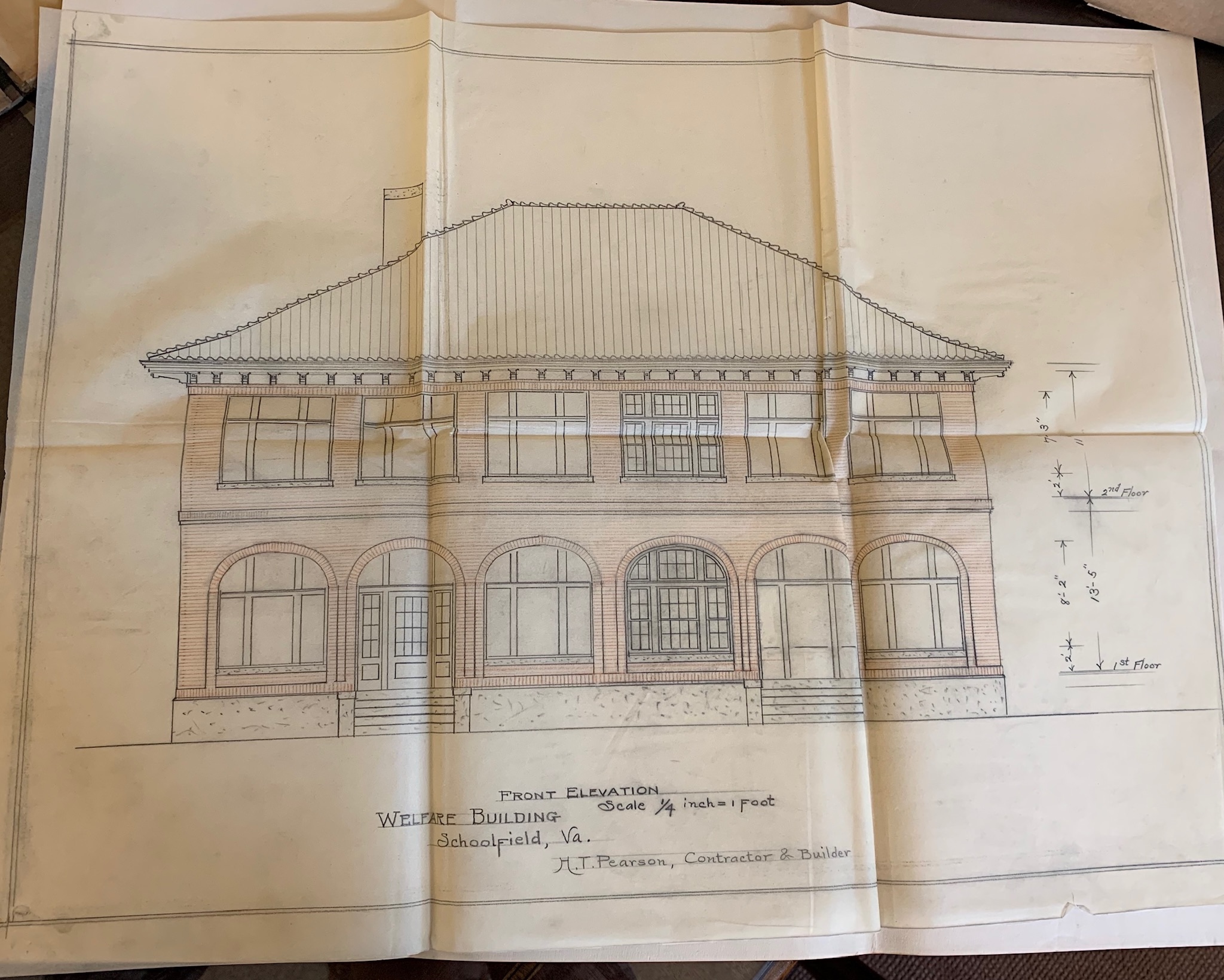

The Welfare Building, later known as the Personnel Building, was designed by J. Bryant Heard and built around 1917. This building reflects influences from both the Mission and Classical Revival styles popular during the era with its arched windows and entrances, as well as its low-pitched hipped roof, clad with red clay tiles and wide overhanging eaves supported by brackets.

The Welfare Building was constructed by Dan River Mills to support the needs of a growing mill village—especially the working mothers, who made up twenty-nine percent of the female workforce, a sizeable percentage of a workforce. From 1917 until about 1940, the Welfare Building became the hub for these working mothers and their families. Its walls hosted a variety of activities and services, everything from rooms for departmental parties, children’s clubs, and kindergarten classes to a medical clinic and bathing rooms (Schoolfield homes did not, at that time, have indoor plumbing, so this was one of the few places to come and take a bath). During the Flu Pandemic in 1918, the Welfare Building was used as a makeshift hospital to care for the ill.

In 1907, Dan River hired a superintendent to run their growing welfare program: Hattie Hylton. Hylton was a no-nonsense woman from Floyd, Virginia and the first superintendent of welfare at Dan River Mills. A “young energetic woman of faith,” Hylton was thirty-five years old at the time she became superintendent of welfare for the textile company’s mill village. Though she never married or had children herself, Hylton was both a mother to Schoolfielders and “wife” of Dan River Mills, the company where she ran welfare programs directed chiefly at children and working mothers from 1907 until 1921. Hattie helped then Dan River president Harry Fitzgerald with the design of the Welfare Building as well as the design of the 1919 women’s boarding house, Hylton Hall.

Almost all the Schoolfield children frequented the Welfare Building when it housed the kindergarten in the first years of its life. Icy Norman, one such child who grew up in Schoolfield in the 1910s, remembered how her millhand mother would drop her off every workday at the Welfare Building. When Icy arrived at the Welfare Building, “trained nurses, real nurses” there—all women—changed her clothes into a uniform similar to the other children. Those women “had a category for each [child]” and ensured control over the daily diet and activities of these Schoolfield children. This kind of regulation of children was common practice in the Progressive Era, when there was much fuss made over the health and homelife of workers and their families.

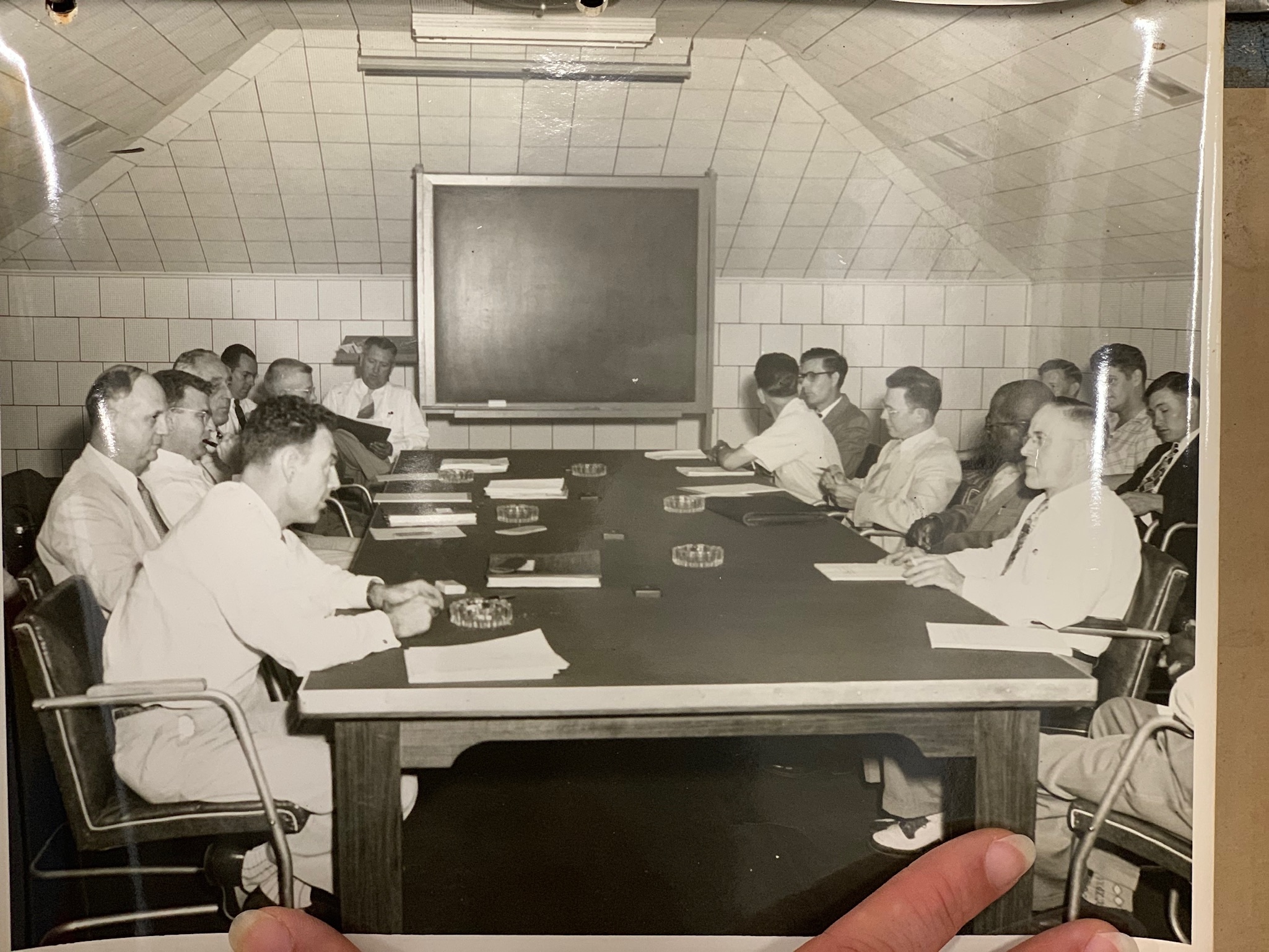

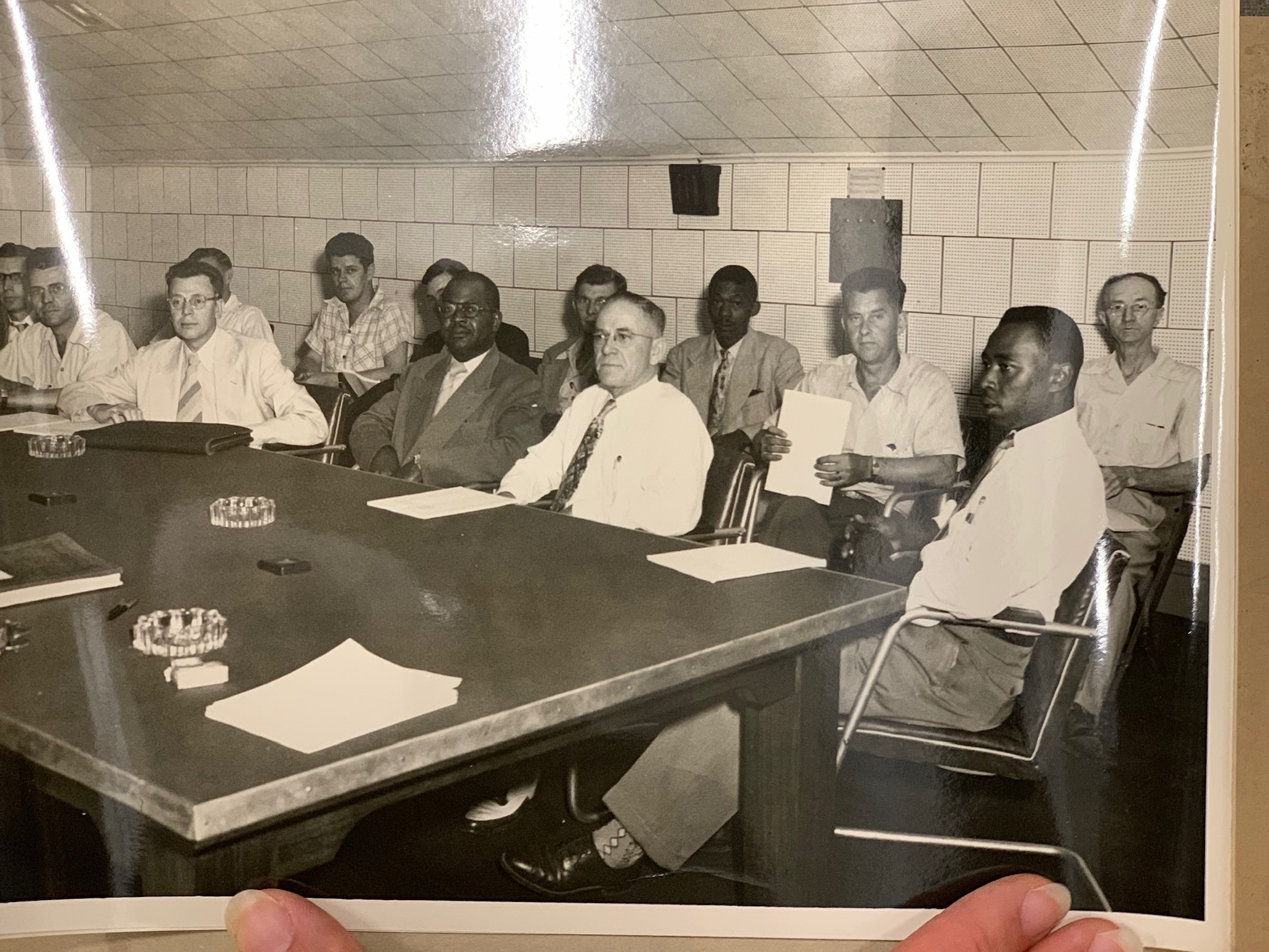

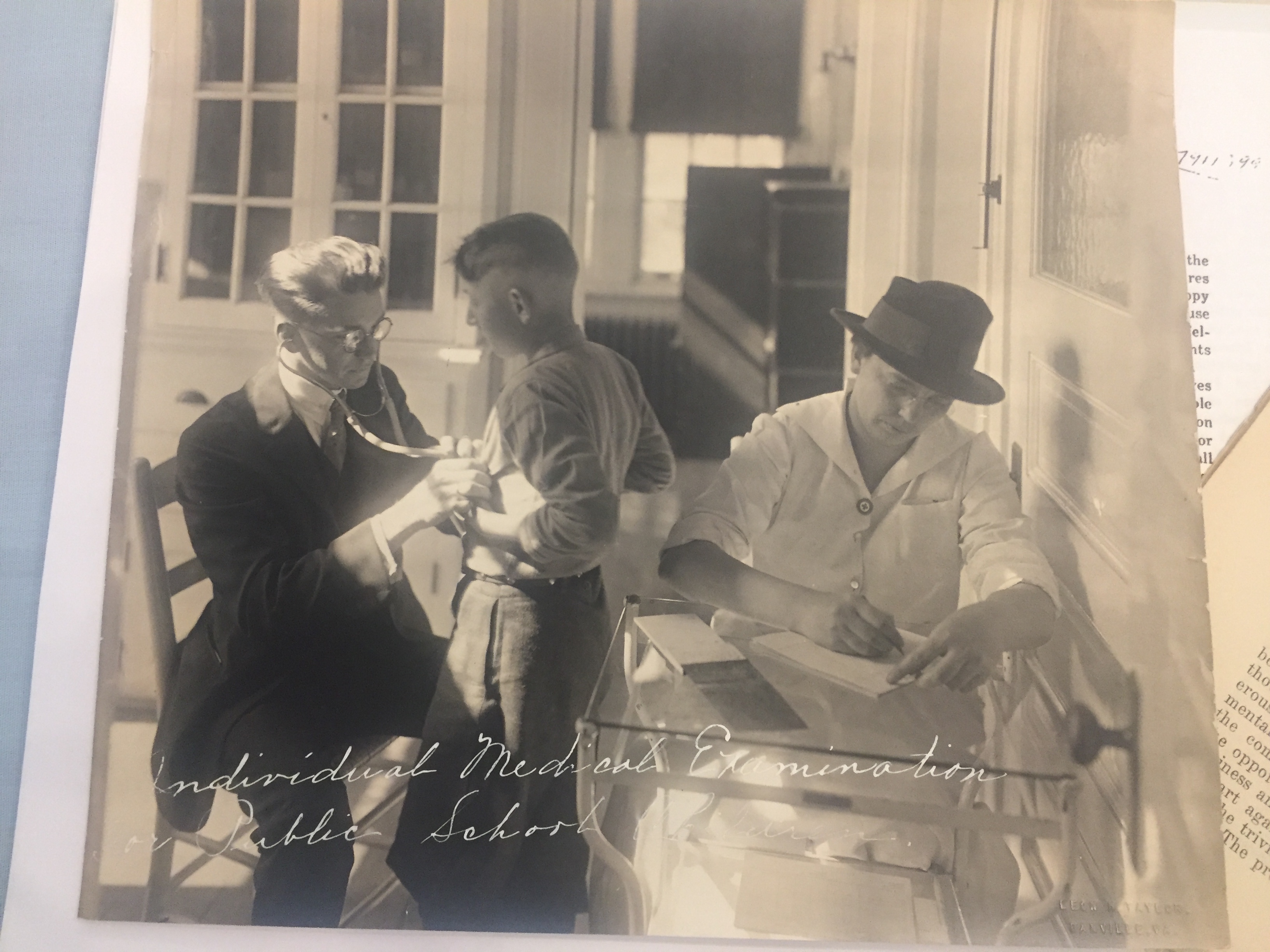

After World War II the Welfare Building expanded as a hub for human resources, labor negotiations, and medical care. The building was the center for draft registration in 1940 and 1941 and was redubbed “The Personnel Building” in 1942 when Dan River refinished the basement and main floor for new personnel offices. Mill work was a dangerous job, and medical clinics were run by the company to address and ameliorate the health risks of working in the cotton mill which often led to hearing loss and the dreaded “brown lung,” when millhand’s lungs were damaged by the cotton particles that floated through the air. The Personnel Building served as a hub for personnel and medical care for Dan River employees until the closure of Dan River in 2006.

After Dan River’s closure, a group of alumni from Schoolfield High School, which had closed in 1954, rallied to preserve the remaining landmarks of Schoolfield. After failing to save the 1916 former YMCA and Recreation Center, the group met preservation success when they purchased the former Dan River Welfare Building in 2008, dedicating it as a museum to the community’s history in 2011.

The Schoolfield Museum and Cultural Center opened in 2011 in the renovated first floor of Dan River’s former Welfare Building. Within the museum were exhibits displaying art, artifacts and other meaningful items such as Dan River rings, pins, and watches given to those who had served ten, twenty, thirty, forty, and fifty-years of their life at the company. There was a Schoolfield band uniform from the 1920s complete with the player’s old trombone, a China set from the former Dan River women’s dormitory Hylton Hall, a girl scout uniform, quilts, and curtains all made up of Dan River fabric.

In 2018, the financial health of the museum waned. A new owner was needed to save the building and its history. In 2019, such a steward was found. To get the building ready for its next use, members of the board and volunteers of the Schoolfield Museum helped inventory, transfer, and accessibly and safely store the Schoolfield collection and exhibits. The museum’s extensive Dan River archive, originally organized in 1982 by a local historian Clara Fountain, was donated to the Southern Historical Collection at the Wilson Library at UNC. Other local documents were stored with Danville Historical Society, and the rest of the Schoolfield exhibit was packed and stored at the Danville Museum of Fine Arts and History with an understanding that certain pieces from the exhibit could be used in the redevelopment of the Welfare Building and other buildings in Schoolfield.

The Schoolfield Preservation Foundation saved, collected and displayed much of Schoolfield’s and Dan River’s history–like this band uniform and Dan River paraphernalia– when the museum was soley housed at 917 W. Main Street.

The Welfare Building and 1938 playhouse in 2020. Photos on file with the City of Danville.

Photo 1: A 1917 photo of the Welfare Building from a Dan River promotional postcard. From the Schoolfield Preservation Foundation Collection. Photo 2: An early rendering of the exterior of the Welfare Building. Courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection Dan River Inc. Papers.

The Welfare Building offered medical service for workers and their families in the village as this 1920s photo shows. Photo courtesy of Judy Edmonds.

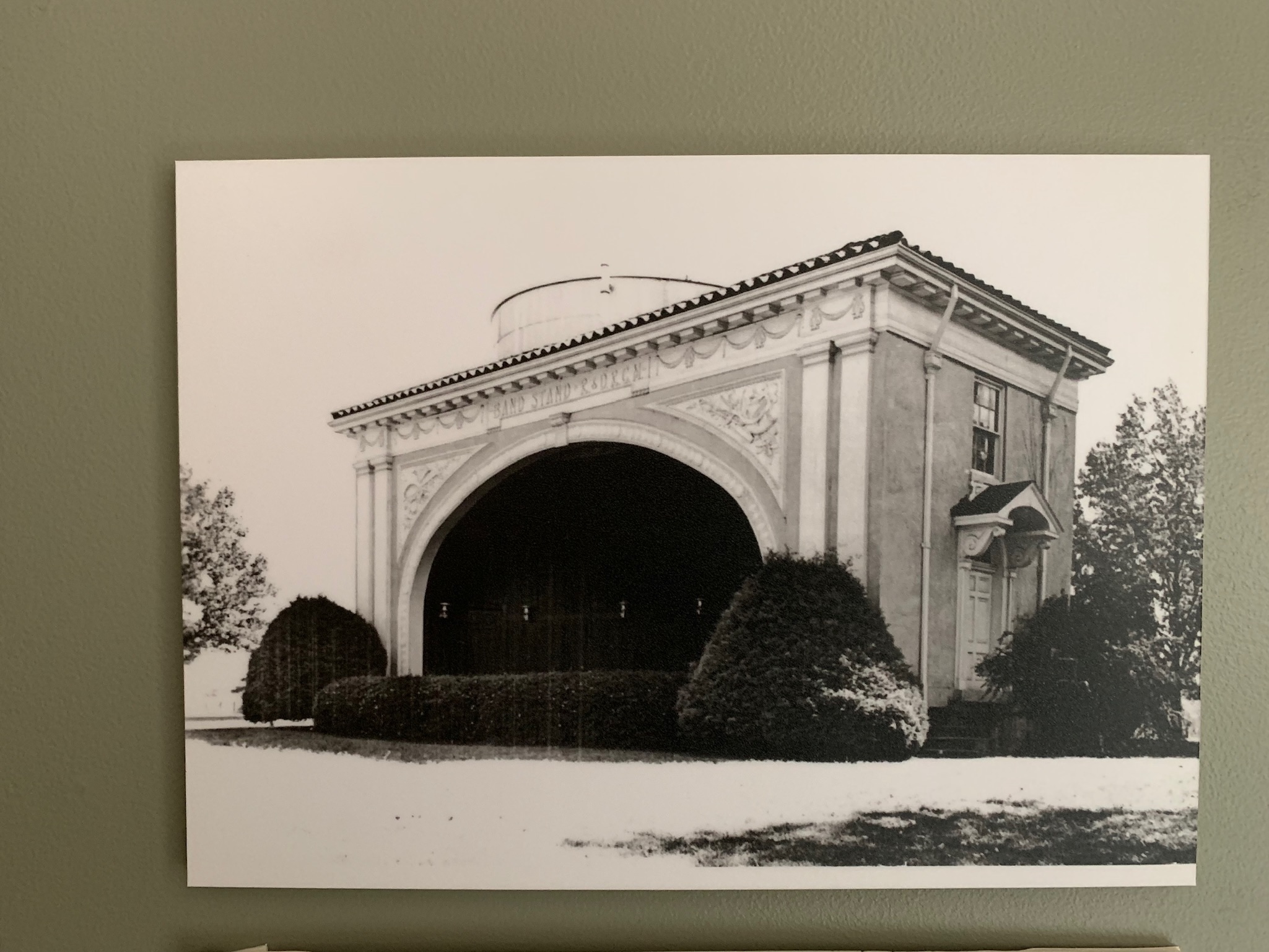

A photo showing the bandstand that stood on the Welfare Building grounds until the 1970s or so. Courtesy of the Schoolfield Preservation Foundation.

Photos from the 1950s labor negotiations that occurred in the attic of what was then known as the Personnel Building. Courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection Dan River Inc. Papers.

See also:

David Clark, ed., “Health and Happiness Number,” Southern Textile Bulletin XXIV, no. 17 (June 21, 1923), Internet Archive, 2013, 8, https://archive.org/details/southerntextileb1923unse.

“Miss Hattie Hylton, Welfare Superintendent: Paternalism in the Cotton Mills,” n.d. Hylton Hall, Danville City 108-5065-0082. Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Richmond.

Herring, Harriet L. Welfare Work in Mill Villages : The Story of Extra-Mill Activities in North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1929.

McHugh, Cathy L. Mill Family: The Labor System in the Southern Cotton Textile Industry, 1880-1915. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Icy Norman, Interview H-36. (#4007), interview by Mary Murphy, April 6, 1979, Southern Oral History Program Collection, SHC., https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/norman/norman.html.

Schoolfield Welfare Building, 108-5065-0083 Nomination Packet, Virginia Department of Historic Resources. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/108-5065-0083/