The Fitzgerald Apartments is a two and half-story apartment building, still in use today, built by Dan River in 1935 in a Minimalist Traditional Style. The building features a U-shaped plan with standing-seam side gable roofs, wood porches and brick exterior. The apartments were built shortly after the death of Dan River Mill president Harrison Robertson Fitzgerald, who died unexpectedly in 1931 and was later honored as the namesake of this building.

Harry Fitzgerald, as he was more widely known, was born 1873 to Martha Jane Hall Fitzgerald and Thomas Benton Fitzgerald, one of the founders in 1882 and first president of Dan River, then known as Riverside Cotton Mills. T.B. Fitzgerald was also owner of a large construction company he had founded in the 1870s and most of the bricks that built the Schoolfield mills bore the name “Fitzgerald.” T.B. Fitzgerald’s son Harry worked his way up through the ranks of Dan River, beginning his work there as an “office boy” in his teens and eventually becoming the mill president in 1918, following R.A. Schoolfield, a Dan River founder and elder mentor of Harry’s.

In the early years of Harry Fitzgerald’s presidency that ran from 1918 until 1931, Dan River management committed to grand schemes to support worker welfare and village life. Fitzgerald had been the mastermind, for instance, in implementing Industrial Democracy at Dan River and encouraged programs such as the Schoolfield Baseball Association that showcased the benefits of Dan River’s paternalism in its reciprocal obligations between management and workers. Fitzgerald’s efforts to support workers earned him much praise in Schoolfield, but a hearing deficit, a religious zeal, and his focus on welfare programming in Schoolfield over profits at Dan River also attracted teasing and criticism from both Schoolfielders and his own mentor, R.A. Schoolfield.

Fitzgerald’s hearing, which began waning when he was twenty-five, was an ailment that hobbled his public persona in the eyes of some millhands, especially as he got older. Fitzgerald learned how to maintain his authority despite his deafness and used a hearing device known as a dictograph at his office, home, and even had these installed in the pews at his Danville church, Mount Vernon Methodist. Apart from these hearing aids, Fitzgerald also learned how to lip-read. Defiant of his hearing loss, Fitzgerald proudly overcame his near deafness for most of his tenure as mill president.

A proud man, who was not the type to “accept afflictions,” Fitzgerald did not give up his passion for oration despite his deafness, and subjected Schoolfielders to annual addresses, weekly sermons, and frequent moral lectures. Claude Chattin, who grew up in the village in the 1910s and later worked as a carder at Dan River, remembered that Fitzgerald was a “very conscientious man” who had “wanted to do well by the people” with his welfare programs. Chattin also remembered how Fitzgerald’s deafness gave him somewhat of a speech impediment that muddled the moral sermons he gave weekly to village children, making him somewhat of a comical figure. Ethel Knick remembered, too, that Fitzgerald would often come to the schools and give lengthy talks even though his speaking voice was “not good…very erratic and you couldn’t understand everything that he said.” Chattin did not mind the lectures, although he got the feeling that Fitzgerald often thought he “knew better than the people.”

Harry Fitzgerald’s religious zeal as a sermonizer and his devotion as congregant and board member of the Mount Vernon Methodist Church transferred to his efforts at the building the welfare program at Dan River. Fitzgerald insisted on continuing and expanding welfare programs during his tenure at Dan River, overseeing the construction of the YMCA, Welfare Building, and Hylton Hall as Treasurer and Vice President. The welfare programming run through these buildings often cost more than it could make. As company profits dipped in 1924 thru 1929, Fitzgerald’s mentor and mill founder R.A. Schoolfield criticized Fitzgerald’s allegiance to his welfare program over the mill’s profitability. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, Schoolfield criticized Fitzgerald again as Fitzgerald was quick to cut millhands’ wages before he cut welfare programs, or his own salary, much against Schoolfield’s fervent advice.

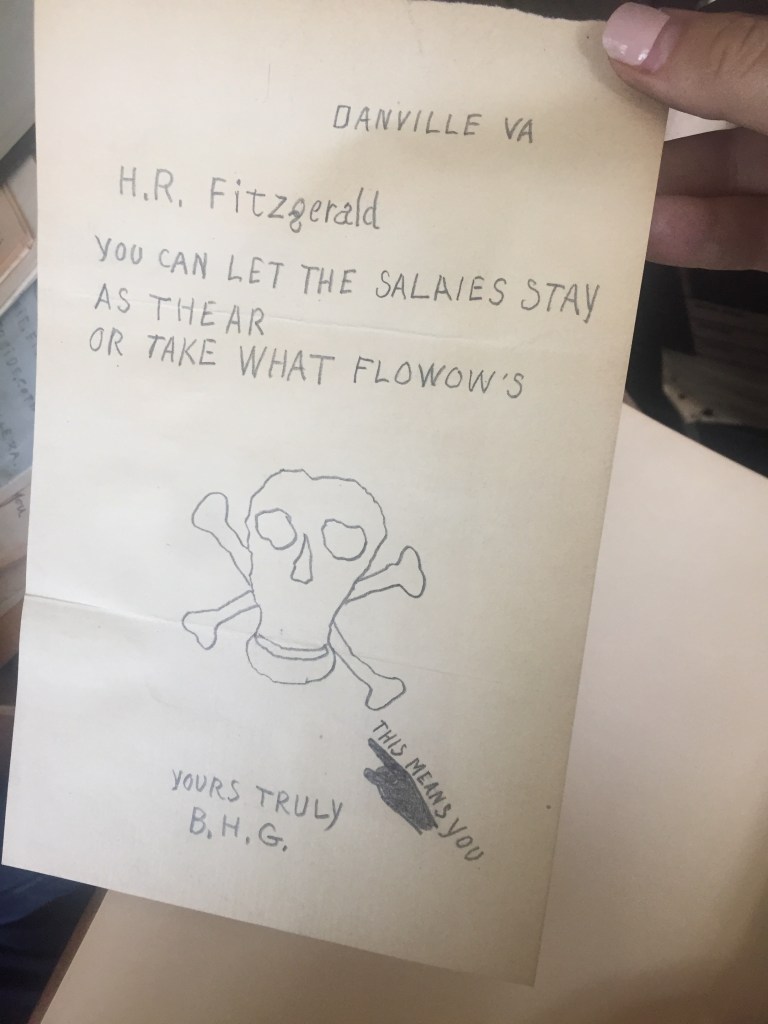

By September 1930, Dan River’s profit loss pressured Fitzgerald to withdraw his previous devotion a paternalistic scheme of welfare programming. To cut costs, he slashed hours and wages and eventually halted welfare programs. This enraged many hard-working millhands who had come to rely on steady paycheck and the welfare programs the mill provided. Over the fall and winter of 1930 and 1931, workers organized and called a strike. During that difficult winter, Industrial Democracy fell apart and Harry Fitzgerald’s vision of a strong bond between employer and millhand was dashed. Throughout the strike, Fitzgerald personally received letters from millhands who recommitted their loyalty to him and the company, but far more often Fitzgerald received death threats and hate mail for the wage cuts he imposed and for rescinding welfare programs.

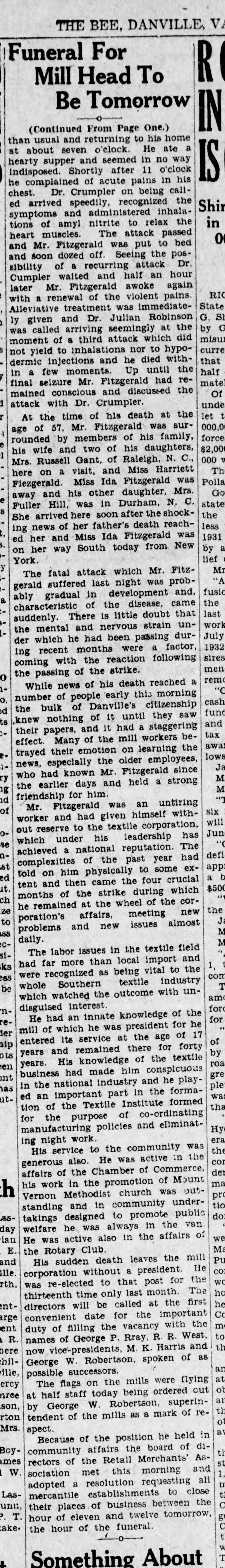

Unfortunately, Fitzgerald’s “acute deafness” and “impediment of speech” had, in the opinion the Danville writer Julian Meade, made it “difficult for him to know what was happening in the mills” during hard times. This deafness may even have helped him avoid any face-to-face labor negotiations that could have ended the strike earlier. When the strike finally ended in January of 1931, however, the damage to Fitzgerald’s hope for a harmonious corporate community was done. Strained and stressed from the collapse of his dream for Dan River and estranged from his mentor R.A. Schoolfield, Fitzgerald died of a heart attack a month after the strike ended. He was fifty-seven. To honor Fitzgerald’s efforts for worker welfare at the company, in 1935 Dan River President Robert West and the company’s board of directors erected these apartments in his name.

A 2020 photo showing the Fitzgerald Apartments at 1236 W. Main Street. Photo on file with the City of Danville.

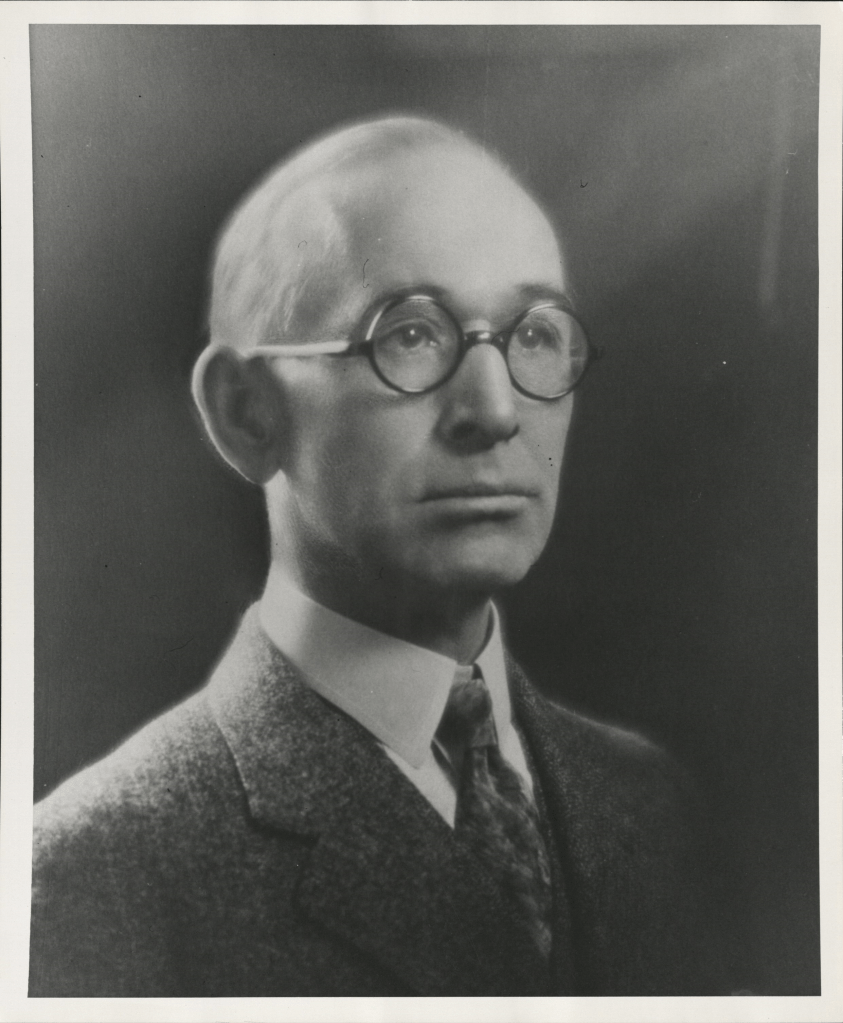

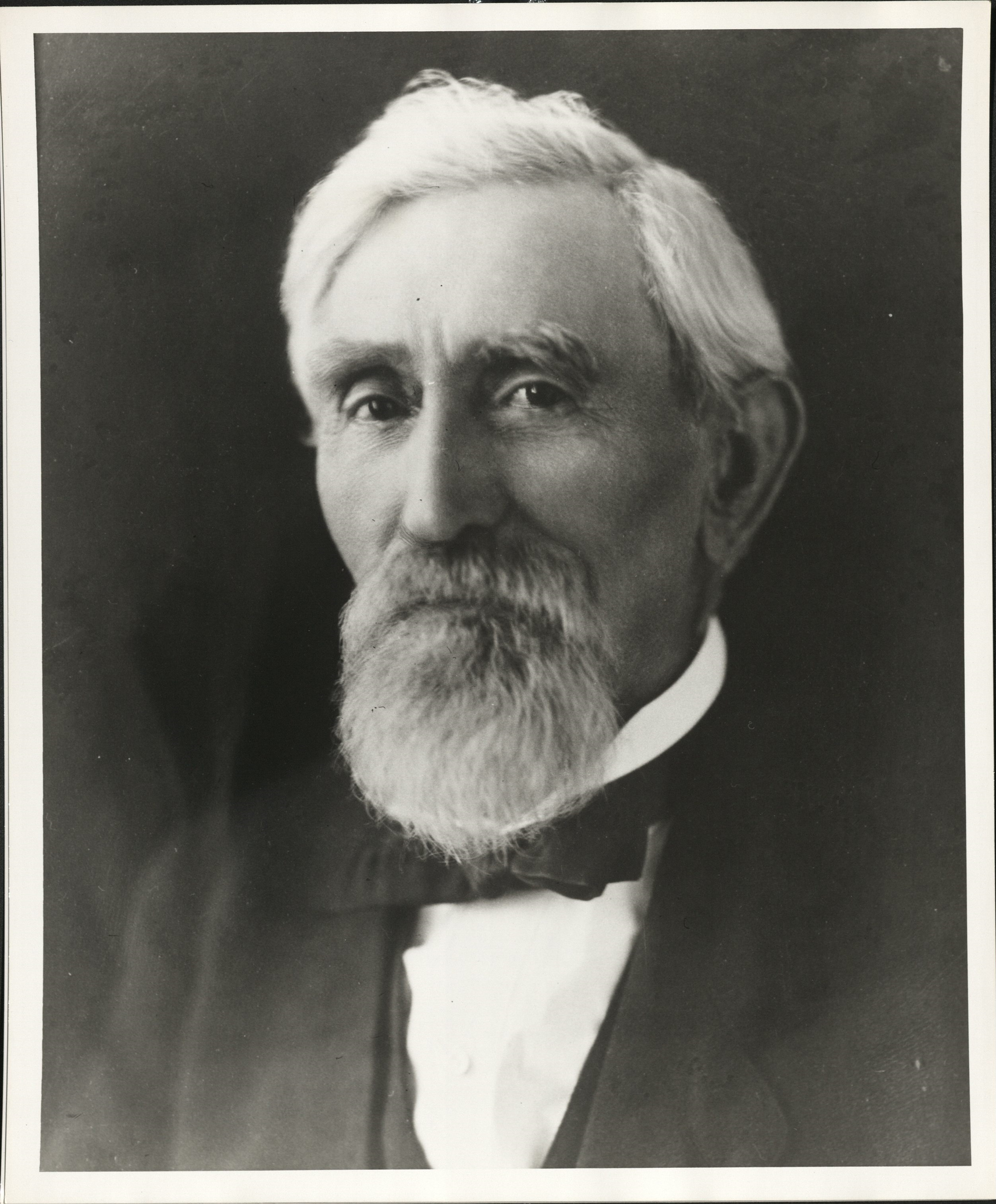

The Fitzgerald Apartments were named for Harry Fitzgerald, the former president of Dan River until his untimely death in 1931. Harry Fitzgerald’s father Thomas Benton Fitzgerald, featured in the second photo, was a founder and also a president of Dan River Mills. Courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection Dan River Inc. Papers.

Tensions ran high in the labor strike at Dan River in the winter of 1930 and 31 as this anonymous letter to DR President H.R. Fitzgerald shows. Courtesy of UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Library’s Southern Historical Collection Dan River Inc. Papers.

Fitzgerald’s untimely death was attributed to the stress of the strike at Dan River. “HR Fitzgerald Dies Unexpectedly,” The Bee. February 24, 1931, p 1. Fitzgerald was so well known and regarded in the textile industry that even the New York Times noted his death (see below). “H.R. Fitzgerald, Textile Man, Dead, The New York Times. February 24, 1931. New York Times Machine.

See also:

Hayes, Jack Irby, and Dictionary of Virginia Biography. “Fitzgerald, H. R. (1873–1931).” Accessed January 25, 2020. https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Fitzgerald_H_R_1873-1931.

“Fitzgerald, T. B. (1840–1929).” Accessed January 25, 2020. https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Fitzgerald_T_B_1840-1929.

Smith, Robert S. Mill on the Dan: A History of Dan River Mills, 1882-1950. Duke University Press, 1960. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x000314340;view=1up;seq=9, pp 410, 554.

Chattin, Claude. Interview by Jack Irby Hayes, 1984. Averett University Collections; Virginia Humanities.

Knick, Ethel Posey. Interview by David E. Hoffman, 1984. Averett University Collections; Virginia Humanities.

New York Times Magazine. “The South: The New Labor and the Old.” June 15, 1930. New York Times Timesmachine.

King, Robert E. Robert Addison Schoolfield (1853-1931): A Biographical History of the Leader of Danville, Virginia’s Textile Mills During Their First 50 Years. Richmond, Virginia: William Byrd Press, 1979.

Meade, Julian R. I Live in Virginia. New York & Toronto: Longmans, Green & Co., 1935. https://archive.org/details/iliveinvirginia008017mbp, p 7-8.